Nevada County, California

Grass Valley, California

Empire Mine

Nevada - COUNTY

State Highway to reach it - PAVEMENT

Grass Valley - GAS

Ride to Empire Mine State Park

One of the longest running gold mines of the Gold Rush Era, Empire Mine operated for over a century from 1850 to 1956 and is said to still contain millions of dollars of gold. The oldest, deepest, richest, and longest, it was also the largest hard rock mining operation in California pulling more gold out of the ground than any other mine of that era. Overall, the mine produced 5.8 million ounces of gold pulled from 367 miles of tunnels which converts to $10,904,000,000 in today's dollars. That's billion with a B.

If you wander around the foothill area, you will invariably pass by Empire Mine as you ride up Highway 49 Yuba Pass headed through Grass Valley and Nevada City on up to Downieville and beyond. Located in Grass Valley, exit Highway 49 and ride up Empire Street east and pull the bike into the gravel parking lot. Much like nearby Malakoff Diggins, the gold was discovered by accident. George Roberts was a lumberman and the story goes while surveying some trees in the area, he happened to glance at his boots and noticed tiny gold flakes on them where the park's main parking lot is now. The gold rush had been on a full year already, however, the miner’s primary source of acquiring the gold at that time was to pan the gold right out of streams and river beds.

The gold George Roberts found was embedded in quartz rock. The only way to get to the gold was to dig it up and crush the rock. By 1851, the land was perforated with hundreds of "coyote holes" - vertical holes in the ground, 20 to 40 feet deep, that resembled water wells. Miners were lowered into these holes in buckets. But this was very difficult for the time and there were better, and easier, diggins elsewhere.

George sold his rights to the land for a mere $350 in 1851 ($11,000 in today’s dollars). Little did he know, he was quite literally standing on a gold mine. George couldn't have known that in a mere 13 years, by 1864, the mine would already have produced one million dollars’ worth of gold. In 1852, the Ophir Hill Mine property was purchased by John Rush, who changed the name to Empire Quartz Hill Company.

In the early 1850s, Grass Valley was populated by a tiny handful of people. Cattle ranchers discovered the region after looking for lost cattle that had wandered into better grassy meadows spurring the name Grass Valley. By 1851, Grass Valley at the 2500 ft level swarmed with over 20,000 residents. Present day population sits at around 13,000. There is gas, food and lodging in Grass Valley.

The hilltop of present-day Empire Mine pulsated with gold seekers looking for easy pickins. But it wasn't so easy- a new and efficient method of extracting the gold from the quartz was in dire need.

The method was Hard Rock Mining, and it befuddled Argonauts who realized this was tremendous hard work. Especially with the tools and knowledge of the day. First you must dig a hole into solid rock. Then the rock you dig up, you have to crush it. Then somehow extract the gold from the crushed rock.

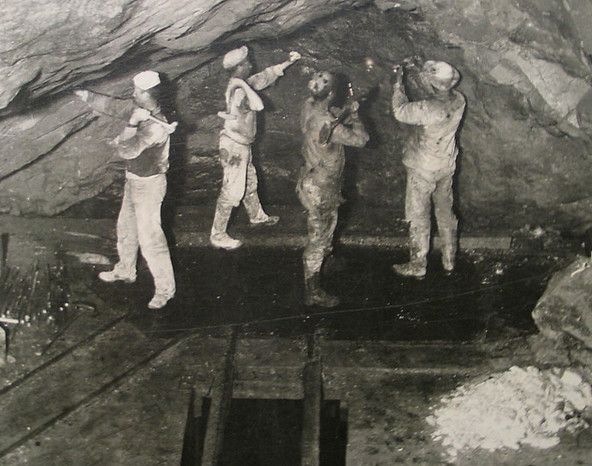

Ancient Egyptians built fires against rock walls, but the cracking caused toxic fumes, exploding rock and dust. Gunpowder blasting started in Saxony in 1627. It was more efficient, but still dangerous. The mining method of the time was two men prepared a powder hole. As one held a heavy drill bit against the rock, the other swung a large hammer to drive the bit into the rock, a process called double-jacking. The man holding the bit then rotated the bit slightly while the other man swung the hammer again. Then the bit was rotated a quarter-turn again, and the process repeated to slowly drill a hole, by hand, into sold rock. An improvement came about with the use of dynamite, which required smaller holes to concentrate the explosive power. One miner, single-jacking, held both the smaller drill and the hammer.

Men intent on mining the quartz rock were rescued with the arrival of Cornish immigrants from the Cornish Peninsula of southwest England. For the past 1000 years, they had pulled tin and copper from their native soil. They brought with them their knowledge of hard rock mining, their work ethic, and their customs. The Empire Mine labor force soon was made up of 90% Cornish miners. Many descendants of these Cornish miners still reside in the Grass Valley area.

Jobs in the mine required both strength and good judgement, and many workers were versatile. A mucker might work up to setting timbers, places charges, or operating pumps. Many were jacks-of-all trades and equally at home in the mill, hoist house, blacksmith or carpenter shop. The Empire Mine introduced compressed-air powered drills in 1890, a decade sooner than most mines. Unfortunately, clouds of rock dust often caused silicosis, a lung disease. Later, improved drills sprayed water to settle the dust.

Skilled blasters could control the amount of rock thrown by dynamite once the holes were drilled and packed. Blasters even learned to direct the broken pieces to land in a specific location. The mucker then shoveled the broken rock, or muck, into one-ton ore cars.

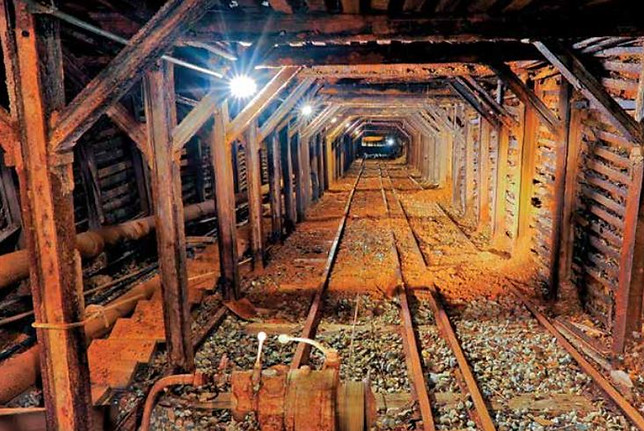

Miners long ago were limited to coyote holes, a vertical hole in the ground. Miners used a bucket hoist to lower themselves into their hole. With improved hoists, cables and blasting materials, miners reached greater depths and built complex underground features such as stopes and wooden lattices underground to hold up the ceiling of rock they were removing. The earliest known mine shafts – around 4000 B.C. – were almost 160 feet deep. The Empire’s deepest incline shaft reached to 4,650 feet. After the Empire-Star consolidation, the mine reached 11,000-foot total incline depth, which was about a mile below the earth’s surface.

As the mining progressed to a feverish pace, the depth of the mine soon fell below the water table. The solution was the Cornish plunging pump, capable of pulling 18,000 gallons of water out of the mine per day. These pumps were powered by steam, which required large amounts of wood. Area forests were then clear-cut to supply the wood needed to power the steam engines. Clear-cutting the forest had the obvious result of running out of trees to power the steam engines that powered the mining operations.

Although electricity was generated at the mine as early as 1895 from the use of Pelton water wheels, Cornish pumps were finally replaced with electrical hydraulic equipment around 1900 after 40 years of use.

Despite the efficient removal of water from the mine, the lattice of timbers used to hold fast the ceiling of the mine tunnels would rot in the damp mine air, producing methane- a colorless, odorless gas that killed when inhaled.

While birds such as canaries were carried into the mine to warn of an increase in methane gas, an unusual relationship also developed with rodents. Miners were known to feed the rats that lived inside the depths of the mine. Much like the canaries carried into Appalachian Mines, a dead rat also gave quick warning to the buildup of deadly methane gas.

Cornish immigrants were fortunate in many ways: they shared a language of those who sought their skills, worked in a countryside much like their home-land, and were numerous enough to maintain their customs. One custom they brought with them was the pasty, a meat & potato pie, which is readily available today in nearby Grass Valley restaurants. Each day, they carried with them their metal lunch tin down into the mine. The lunch pail had several levels within it. Using a candle, miners heated the bottom of the tin, in turn heating the pasty.

The Cornish valued self-sufficiency and some thought them clannish, but this unity led to stable communities. The church was usually their first public structure. A love of music and literature was expressed in church choir preparation and Bible study. Miners often sang hymns as they rode into the mine on skips. The Cornish were also less politically active than the Irish, but were attracted to fraternal groups, such as the Elks and Odd Fellows Lodge. Miners joined the union but emphasized its social and benevolent roles.

The hard rock Cornish miners worked a life of hard work in a dangerous occupation. During peak years in the life of the mine, they worked six days a week and ten-hour days in the moist, gloomy underground tunnels.

Mistakes in entering or leaving a shaft could be fatal. Miners held their heads low and their arms tucked in during the manskip’s speedy descent. Cave-ins, fires, and equipment failures were always possible. Prolonged exposure to dangerous fumes and rock dust also took its toll on Cornish miners.

Though independent and self-reliant, the Cornish were very loyal to each other. A miner often risked his own life to rescue a fellow worker, confident that his mate would reciprocate if necessary. Trade unions were less aggressive in Grass Valley than elsewhere, but the Empire’s miners went on strike in 1869. Management wished to use ‘’giant powder” – dynamite – which the miners resented because of its fumes and because its smaller drill holes made the double-jack partner teams unnecessary. The miners won until 1872, but dynamite was increasingly used in other mines of the time. Then a coming depression and abundant labor further compelled its acceptance.

In 1899, Mules were introduced within the depths of the mine. At one-year-old, they were taken down into the maze of tunnels and spent the rest of their life there. They soon became an essential part of the work. They had their own clean stalls, fresh food and water. The mules were also very temperamental. Miners kept handfuls of oats, a shot of whiskey, and the mule's favorite- a snuff of tobacco. A miner trying to walk past a mule might be stopped in his tracks by the mule bloating its stomach in the narrow passage. A little payoff was all that was required for passage.

If a miner might try to fool the mule into pulling 7 tons instead of 8 tons of ore- the mule knew. Until the extra car was unhitched, and the mule was compensated with a quid of tobacco- the mule wouldn't budge. After that, the mule would diligently pull the 7 cars with all its might.

The men responsible for the immense success of the mine were the owner William Bourn, Jr. and his mine superintendent George Starr, who was also Bourn's cousin, and was referred to as Cap'n. Bourn inherited the mine at age 21 in 1877 from his millionaire father. Bourn Sr had died from an accidental self-inflicted gun shot wound. Bourn Jr headed to England to attend Cambridge University and when he returned, he took over the mining operations at the Empire.

Bourn ran the mine and was also an investor in the Spring Valley Water Company. He also headed up a merger into what would become Pacific Gas and Electric Company. He also built numerous homes, one of the best known is the Filoli country estate in the Bay Area near Palo Alto.

Starr also started early but far from the silver spoon. At age 19 in 1881, he began working in the mine as a mucker- the dirtiest and most difficult job in the mine of cleaning up the debris from the tunnels and shafts.

By age 28 years old- he became the mine superintendent. Starr would be credited with an endless stream of innovations. Miners called him a "Mining Genius" and the "Shining Star of the Empire". Geologists and engineers from around the world ventured to Grass Valley to view the latest technologies being used at the Empire.

With the introduction of dynamite into the Empire Mine in the 1870s, this evolved the mining methods to single jacking. This change allowed for only one miner being required to hammer a series of small holes into the rock face to be packed with dynamite, then exploded to release the rock.

George Starr left the Empire Mine in 1893 to supervise a gold mine in South Africa. Then, on his way to Alaska in 1898, Starr stopped in San Francisco to visit his cousin. Bourn persuaded Starr to return to the Empire, where he served again as superintendent. He remained at the Empire for the next 30 years.

By 1890, single jacking was replaced with compressed-air powered drills to carve holes into the walls of rock. Later, these evolved to an improved design that sprayed water onto the drill bit to keep down clouds of dust created by earlier designs.

Even common things such as mine cars were improved to make the mine more efficient. Standard mine cars were modified to have their own bucket system. Muckers scooped the ore into buckets that rested on the ground. Once full, the buckets cantilevered the ore into the mine car rather than having to shovel the ore up into the car, allowing miners relief of the backbreaking work.

The mine was pushed further and further soon extending 11,000 feet on the incline and a mile below the surface in a maze of 367 miles of tunnels.

In order to extract the gold, the ore was brought to the surface, then crushed in a massive stamping mill. Much like the stamp press pictured above, by 1930, as many as eighty stamps were utilized at one time to keep up with production.

The stamp mill today is nothing more than a pile of rubble, but its foundation is clearly visible. There is a stamping press that's been brought to the site to view if you've never seen one before. Once you look at it, you have to imagine 80 of them lined up and crushing rock 24 hours a day. The Stamp Mill was enlarged and remodeled several times, eventually becoming one of the largest of its kind in California.

There were eighty stamps and many weighed nearly a ton, giving the mill a combined dropping weight of 5,500 tons per minute. Once the quartz rock was crushed into a powder, the fine grit was then washed onto copper tables coated with mercury, also known at the time as quicksilver. Quicksilver was a rock ore that was mined in places like New Iridia along Panoche Rd which was supplied in great quantities to help fuel this chapter in Gold Rush history. Gold adheres to mercury (quicksilver), so after the gold ore was crushed by the stamps, the fine powder was washed across copper tables that were coated in mercury. The accumulated materials were then scraped off.

This combination of metals called an amalgam was next taken to the retort room, where heating caused the mercury to separate from the gold. The end result was pure gold, and lots of it.

Mercury from the stamp mill was recycled, and the remaining sponge-shaped gold nuggets were cast into 89-pound bars and taken to San Francisco’s U.S. Mint. In 1905, Empire adopted a more efficient mining method. In this process, cyanide was used to dissolve gold while it was embedded in the quartz. The gold could then be leached out of the quartz ore in a liquid form. The cyanide method is still in use around the world.

As the mine grew larger, the tunnels extended to over 367 miles of labyrinthine pursuit of the veins of gold, spanning to five square miles of underground workings. There was no computer modeling in 1890. This maze of tunnels was kept track of by hand in a place called the Secret Room.

A model of the mine the size of an entire room was built to scale of what lay below the surface. The model represents five square miles of underground workings. When visitors go down the actual shaft in the park, they have journeyed only "one inch" on the model. Anything past "two inches" on the model is underwater in the actual mine.

The windows were blacked out thus earning the room its title. Few people even knew the room existed while the mine was in operation. Today, the immense model is an intensely fascinating relic left behind in the present-day museum.

The interior of the mine below ground isn't open to tourists, although the main opening is lighted to allow you to peer down into the depths of the mine. The lower levels are now filled with water after the mining ended, and the water table rose into the mine once the pumps stopped continuously pumping the water out.

Currently, an 800-foot shaft has been cut into the hillside. Known quite simply as the Underground Tour Project, the plan was to transport visitors through the new shaft and give a fresh hands-on experience to life inside the mine. The plan was, after viewing several dioramas of mining life and operations along the way, a tram finally reaches the main shaft where visitors can view the quartz vein which was mined upwards creating a large cavernous room called a stope. The tram would have carried 24 people at a time with hard hats and rain slickers part of the tour.

The state of California spent $2.5M, obtained from grants and donated money, on the project until 2012 when the state fire marshal found steel beams installed to shore up the tunnel were corroding and determined to be unsafe. The state then determined it would take another $1.4M to fix the issue and killed the entire project, much to the chagrin of local supporters who felt the mine tours would be a terrific new draw for tourism.

After visiting the museum, walk up the path to the Bourn Mansion pictured above. Built entirely of waste rock from the mine, the home is a beautiful example of late 1890s architecture. This English manor home was called a cottage to distinguish it from Mr. Bourn’s other homes. The main floor holds the kitchen, service rooms, living room, dining room, and a reading room later used as a bedroom by Mr. Bourn, Jr. Four bedrooms and two baths are on the second floor. The servants’ rooms and a bathroom were located above the kitchen.

Designed to resemble an English country lodge, the home was built by Willis Polk. Between 1898 and 1905, the grounds were expanded to include a greenhouse, tennis courts, bowling alley, squash courts, and reflecting pools. William Bourn, Jr. built the clubhouse for use by his supervisory personnel and as a place to entertain visiting guests. The 1905 clubhouse is still used by the Empire Country Club and for park special events. The Bourns loved trees and flowers of all kinds. The nearly 1,000 vintage rose bushes seen in the formal garden and on the landscaped grounds were cultivated in their greenhouse. On weekends, docents in Edwardian dress provide tours of the interior of the home, restored and preserved in 1890s condition.

Surrounding the home are 13 acres of gardens and manicured lawns, impossibly green in Springtime. Visit when the roses are blooming in the expertly cared for Rose Garden. The reflecting pools, with the water dyed blue, also capture a glimpse of an era long since passed. As beautiful as the home is, William Bourn, Jr, only used the home two to four weeks out of the year. He simply found the deafening noise from the nearby stamp mill too much to handle.

He instead lived most of the year in San Francisco at the Fioli Mansion near Palo Alto. It was named after his motto of "Fight, Love, Live." There's a small museum that all visitors should check out. It includes several placards, ample period photographs, and the Secret Room, pictured above, still in its original location.

During summers, tours are given at intervals by knowledgeable docents who are either park rangers or volunteers. The walking tour may include strolling down into the entrance of the mine and through some surrounding buildings. Then continue on through the inside of the Bourn Mansion. The park is said to attract 100,000 visitors a year. Check the park website for hours (normally 10-5) and special events.

Around Thanksgiving to Christmas, the grounds are decorated for the festive season. Tours this time of year include hot cider and cookies.

There are 14 miles of hiking trails surrounding the 856 acres the State of California now owns. After the mine closed in 1956, the property sat idle for 20 years until the state of California paid $1.2M for the mine in 1975 and turned it into the present-day state park The state, however, does not have the rights to anything below ground, namely the Empire Mine. Newmont Mining retained the mineral rights to the Empire Mine beneath the park.

Nearby Motorcycle Roads:

Be sure and ride Yuba Pass - Highway 49. If you are headed due north, you can connect up with Oregon Hill Road to La Porte Road which is the latest motorcycle mecca with new pavement on up to Quincy.

North of Empire Mine is Tyler-Foote Crossing Rd which runs up to Malakoff Diggins. The longest single span covered bridge is nearby in Bridgeport via Pleasant Valley Road.

South of Grass Valley outside of Auburn is Foresthill Road, which runs up to Mosquito Ridge.

Empire Mine State Park

10791 Empire Mine St.

Grass Valley, CA

530-273-8522

Empire Mine - Photo Gallery

MORE INFO: Empire Mine State Park

GPS LOCATION

39°12′13″N 121°2′34″W - Empire Mine

Empire Mine State Park

10791 Empire Mine St.

Grass Valley, CA

530-273-8522

RELATED INFO:

Topo Maps